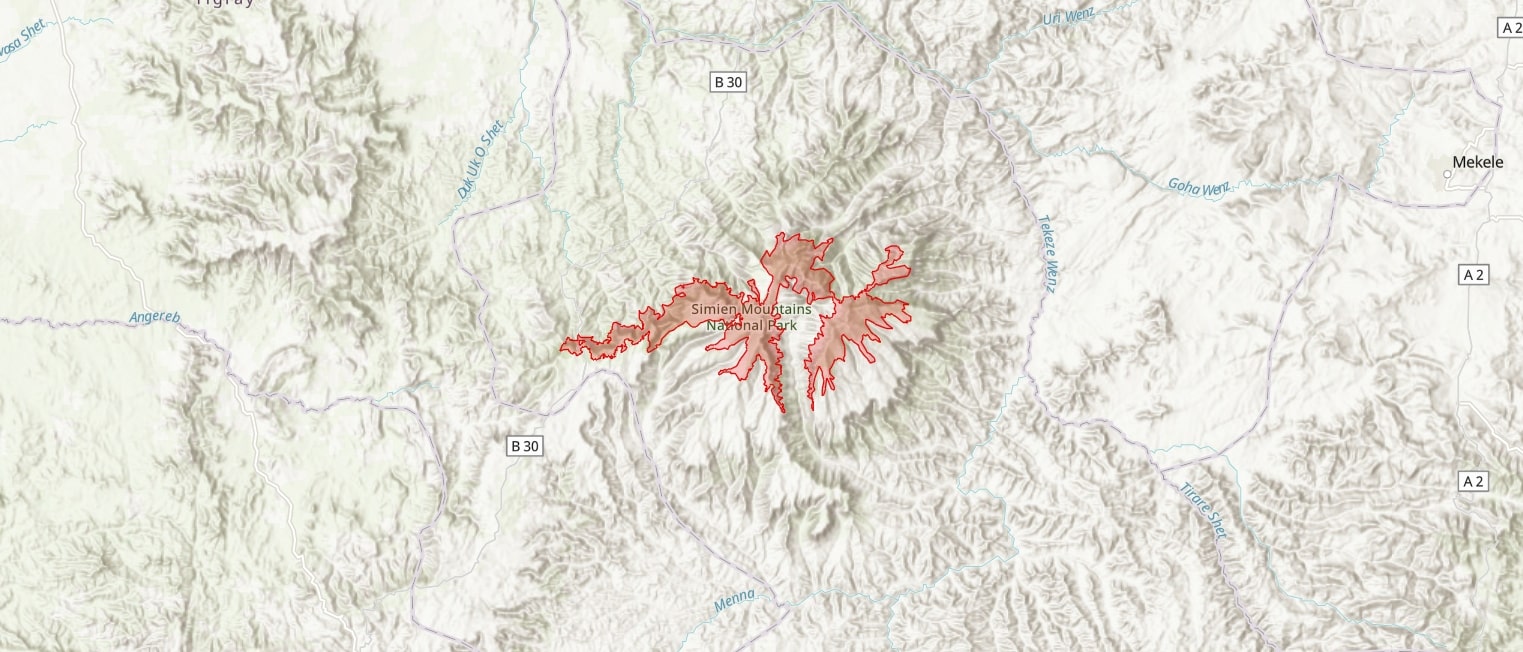

Country: Ethiopia

Administrative region: Amhara (Regional State)

Central co-ordinates: 13.22700 N, 38.33830 E

Area: 611km²

Qualifying IPA Criteria

A(i)Site contains one or more globally threatened species, A(iii)Site contains one or more highly restricted endemic species that are potentially threatened, A(iv)Site contains one or more range restricted endemic species that are potentially threatened, B(iii)Site contains an exceptional number of socially, economically or culturally valuable species, C(iii)Site contains nationally threatened or restricted habitat or vegetation types, AND/OR habitats that have severely declined in extent nationally

IPA assessment rationale

The Simen mountains qualify as an IPA under category A, B and C. The presence of 36 threatened species: 2 Critically Endangered, 14 Endangered and 20 Vulnerable trigger sub-criterion A(i), while the presence of 4 highly range restricted endemics and 7 range restricted endemics currently unassessed or assessed as Data Deficient trigger criteria A(iii) and A(iv) respectively. 3 of these threatened taxa also qualify for B(iii) as they have been listed as socio-economically important species. 12 taxa are currently known to be strict Simen Mountains endemics, representing 2.6% of the national list. Finally, criterion C(iii) is triggered by the presence of a severely declined vegetation type within the IPA, Afroalpine vegetation, for which the Simen Mountains is one of the most intact remaining examples.

Site description

The Simen Mountains (also variously mentioned as Simien, Semien or Semen) are located in the north of Ethiopia, in the North Gonder Administrative Region, 110 km NE of the town of Gonder. Characterized by high plateaus, steep escarpments and gorges, the varied biophysical features found at the site span a large altitudinal range that offers a mosaic of habitats conducive to high floristic diversity and endemism (Puff & Nemomissa, 2001). The Simen Mountains have been recognized for their significance with national and international protection as a National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site. The area referred to as the Simen Mountains usually refers to these protected areas in the highest parts of the Simen Mastiff however this is only a part of the extensive plateaus (UNESCO: 13,600 ha; National Park: 41,000 ha, TIPA: 61,100 ha). The Simen mastiff consists of plateaus c 3000 m high, reaching their highest peak of the is Ras Dejen (4543 m), the highest peak in Ethiopia and fourth highest peak in Africa. Other notable mountain peaks in the IPA include Mt Bahwit (4430 m) and Mt Silki (4420 m). The Jinbar River divides the main plateau flowing south, Menesha river bisects the peaks of Ras Dejen and Mt Bwahit flowing north and the Seraweka, Belegez and Wazla Rivers flow north-east.

The Simen Mountains IPA is of global conservation significance as one of the best remaining examples of Afroalpine and Afromontane vegetation in Ethiopia, which in turn is important habitat for many threatened and endemic taxa.

Botanical significance

The Simen Mountains IPA falls within the Eastern Afromontane biodiversity hotspot. This IPA contains high endemism (notably within Asteraceae and Poaceae) and floristic diversity as a result of the mosaic of different habitats present at the site. The mountain acts like a sky island refuge, harboring 12 strict Simen Mountains endemics and 65 taxa endemic to Ethiopia. While much of this diversity lies within the existing National Park boundary, the IPA boundary has been extended, where possible, to include native vegetation and IPA trigger species records.

The Simen Mountains are of global botanical importance for holding the entire known populations of 12 endemic plants, namely Afrovivella semiensis, Cenchrus beckeroides, Cineraria sebaldii, Crepis xylorrhiza, Echinops buhaitensis, Gymnosporia cortii, Lobelia schimperi, Paronychia bryoides, Pimpinella pimpinelloides, Poa pumilio, Snowdenia mutica and Swertia engleri. Unfortunatley a Simen endemic herb, Swertia scottii, has been assessed as Extinct, showing the urgent need for careful conservation management of the floristic diversity within this IPA.

There are a significant number of threatened species recorded at this site, with a known total of 36 threatened species (2 CR, 14 EN, 20 VU) collected within this IPA. A further 4 endemic species have been assessed as Data Deficient, all of which qualify under Criteria A and may potentially be threatened, pending further study. Notably, this IPA is a critical site for the conservation of a two Critically Endangered species, including the grass Poa pumilio and aster Crepis xylorrhiza. Both of these species have only been recorded from Mt Bahwit.

A significant proportion of the Simen Mountains endemics have not been recorded since the type collection, suggesting that these taxa are scarce, taxonomically invalid or possibly extinct. These include Cenchrus beckeroides (DD), Cineraria sebaldii (NE), Crepis xylorrhiza (CR), Gymnosporia cortii (DD), Snowdenia mutica (DD), Swertia scottii (EX) and Poa pumilio (CR). Additionally, Vernonia buchingeri (DD) is known from 2 collections, with the latest record dating over 100 years ago, Crepis achyrophoroides (EN) has not been collected at the site for 160 years, Disperis meirax has not been recorded for over 50 years and Cyperus clandestinus (EN) has not been collected in the Simen Mountains for 200 years. Further study and targeted survey is urgently needed to relocate extant populations and assess their conservation status.

Habenaria montolivaea (VU) has been recorded c. 20 km outside the boundary of this IPA, and there are a few other records from the SMNP cannot be accurately georeferenced. It occurs c 1000 – 2600 m asl which is on the edge of this IPA boundary. While this species may occur within this IPA, it has been left out of this assessment due to this uncertainty that it is still extant at the site. Additionally Vernonia buchingeri (DD) and Verbascum arbusculum (DD) may also occur within this IPA, however specimens for these taxa could not be georeferenced with adequate accuracy to be included in this assessment.

Taxa recorded at the site that trigger Criteria B(iii) as they are socially, economically or culturally valuable species include Afrovivella semiensis and Verbascum stelurum which are utilised for medicine (Hiwot Ayalew et al., 2022), as well as Festuca macrophylla (VU) which is a culturally important building material.

This IPA is one of the best remaining intact examples of alpine vegetation, 97% of which has been has been lost in Ethiopia (UNESCO, 2023). This IPA has a botanical affinity to other Afroalpine IPA sites in Ethiopia, namely the Bale and Arsi Mountains. Despite the rift valley mountains separating Simen and Bale, the two IPAs share X taxa exclusively, and the Arsi Mountains also share X taxa. Many East African Afroalpine species have widespread distributions, however many of these taxa have large interpopulation genetic distance and poor intrapopulation genetic variation, indicative of sporadic long-range dispersal and genetic bottlenecks (Brochmann et al., 2022). Thus, the Afroalpine flora harbors unique taxonomic and genetic diversity that is particularly fragile.

Historically the Simen Mountains were a significant site for collecting activity, with c 220 type specimens originating from the area (Puff & Nemomissa, 2001) however, until recently botanical collecting activities were hindered due to political instability. The uplands and plateaus are well studied, however little is known about the species that occupy remote areas of the lowlands, as the terrain associated with such remnant native vegetation is extremely challenging (Puff & Neomissa, 2005). For detail on the ecology of plants in the Simien mountains, refer to Puff & Nemomissa (2005).

Habitat and geology

The vegetation within Simen Mountains IPA can be categorized into three broad types: Afroalpine grassland, Ericaceous scrub and Afromontane forest (Hedberg, 1951; Puff & Nemomissa, 2005; EBI, 2022). The plateaus and high mountains (c 3200m – 4500m asl) are dominated by Afroalpine vegetation, the slopes and escarpment are dominated by Ericaceous scrub, and the lowlands (below 3000 – 2000 m) are characterized by Afromontane forests. Of these vegetation communities the Afromontane vegetation harbors the highest species richness, whilst the Afroalpine vegetation holds comparatively low diversity but high endemism (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005; Smith & Young, 1987). These patterns of diversity and endemism reflect the steep elevational gradients, microhabitat heterogeneity and insularity present at the site (Jacob et al., 2014).

The Afroalpine grasslands are dominated by a cover of cold-tolerant C3 perennial tussock grasses, herbs, small shrubs, lichens and bryophytes (Smith & Young, 1987). Common taxa include the grasses Festuca abyssinica and F. macrophylla, herbs such as Trifolium spp. and occasional dwarf sclerophyllous shrubs such as Helichrysym citrispinum (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005). The high alpine areas are characterised by the distinctive rosette and cushion plant forms; including charismatic giant tree-like Lobelia species (L. rhyncopetalum and L. schimperi) for which the Alpine areas of East Africa are renowned. These habitats correspond to units mapped as the Afroalpine belt (Friis et al., 2010).

The upper tree line ecotone is formed by trees/shrubs from the Ericacae family, Erica arborea and E. trimera, interspersed with other woody species such as Hypericum revolutum (Miehe & Miehe, 1994; Puff & Nemomissa, 2005). These areas correspond to units mapped as the Ericaceous belt (Friis et al., 2010).

Two distinct types of Afromontane forest can be distinguished in the Simen lowlands, namely a ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ type. The ‘wet’ forests have a species-rich woody layer occur on north facing slopes and in shaded gullies, characterized by Prunus africana, Astropanax abyssinicus, Olea capensis subsp. macrocarpa and Pittosporum viridiflorum. The ‘dry’ forests typically occur on south-facing slopes have a comparatively low canopy diversity, with Olea europea subsp. cuspidata the only dominant tree (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005). These areas correspond to units mapped as Afromontane undifferentiated forest and shrubland, and Dry Evergreen Afromontane Grassland and Forest Complex (Friis et al., 2010).

Geologically, the Simen Mountains are the remnant of ancient shield volcano formed by uplift 75 million years ago (Hurni, 2015). The resulting mastiff is composed of trap basalts that overlie Mesozoic sandstones, which in turn rest on the Precambrian basement (Hurni, 2015). The basalt layers, c 1000m thick in some areas, have eroded extensively over time, resulting in the dramatic landscape of steep precipitous cliffs, deep gorges and jagged peaks present today (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005; Hurni, 2015) The black-dark brown Andosol soil type is prevalent across the site (Hurni, 2015). Additionally, paleo-glacial deposits are widespread throughout the Simen Mountains and can be observed in the Afroalpine grassland regions of 3000-4200 m asl (Hurni, 2015).

The climate at the site is defined by a wet and a dry season. Generally, the climate of the Simien Mountains could be classified into four altitude based climatic zones: Wurch zone (above 3700 m asl) alpine climate; High Dega zone (3400 - 3700 m asl) cool climate; Dega zone (2400 - 3400 m asl) temperate climate; and Woina Dega zone (1500 – 2400 m asl) sub-tropical climate (AWF, 2015). In the Alpine and Wurch zone, plants are adapted to a harsh diurnal climate. Through the year days are very warm and temperatures in the night are often below freezing. This diurnal cycle acts as a strong species filter (Hedberg, 1970; Brochman et al., 2022).

Conservation issues

The Simen Mountains have been recognized for their unique and outstanding biodiversity as a National Park (NP) (1969), UNESCO World Heritage Site (1978), Important Bird Area (2001) and Key Biodiversity Area. Since its inception, the NP boundary has gradually expanded to encompass a broader area. The NP was primarily established to protect endangered and endemic mammal species, and as such left out sites of botanical importance such as Mt Bahwit. In 2007 the NP border was extended to include the majority of the Simen Mastiff and it’s significant botanical sites, and there is a proposal to extend the UNESCO site to this same extent (UNESCO, 2023). To date, management of the SMNP is largely focused on conservation of endemic mammals.

Despite formal protection, the plant diversity in this IPA continues to be under threat from anthropogenic pressures. In the last 40 years human populations in the SM have increased by 400% (IUCN, 2020). Unsustainable utilisation of the IPA lead to it's listing as a World Heritage Site in Danger from 1997-2017. While it has now been taken off the list, analysis of change in landscape cover (from the period 1966–2009) indicates that the contemporary landscape is under pressure (Jacob et al., 2017), and while conditions may be gradually improving within the IPA, they still remain a concern (UNESCO, 2023). Threats to the IPA are well documented and include civil conflict, agriculture and grazing, logging and wood harvesting, erosion, climate change, altered fire regimes, urbanization and invasive species (UNESCO, 1984–2023).

Civil conflict has intermittently affected Ethiopia with varying levels of intensity. This unrest has presented many indirect and direct threats to the conservation of flora. Civil unrest has directly impacted infrastructure and inhibited visitation to the site (UNESCO, 1983-1999). It has also indirectly caused increased migration into the area, heightening anthropogenic pressure on the site. The IPA is remote, and conflicts have triggered migration to the area in search of safety (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005). Communities in the SM still continue to be intermittently affected by violent conflict, and the remoteness of the site limits access to socio-economic services such as education and health, exacerbating poverty and livelihood insecurity (Guinand & Lemessa, 2001; Hurni et al., 2008). Management of the SMNP has generated hostility from local communities who once relied on these areas for grazing, wild-harvesting and subsistence farming. Currently, there is limited local participation in management and governance of SM (UNESCO, 2022), as such increased community involvement and investment in conservation of the SM is crucial for better environmental outcomes at the site.

The Ethiopian highlands have a long history of human interaction and use, and the Simen Mountains have been inhabited for at least 2000 years (Friis et al., 2010). Soil degradation has been devastating over the centuries and continues to be a major threat (Hurni, 2015). The thick humus rich black soil once present at the site has now been heavily degraded due to clearing of vegetation and farming practices over the millennia. Water and soil conservation measures were introduced in the mid-1970s, however high rates of erosion continue (Hurni, 2015).

Due to the remoteness of the highlands, many communities in the area rely on the land for subsistence. Agriculture covers most of the highlands, with most remaining natural habitat occurring on steep slopes and alpine zones above c 3,000 m asl where cultivation is less feasible (Google Earth, 2024). Cultivation is predominately restricted to the edges of the IPA, especially following the relocation of Gich village in 2015–2016 (IUCN, 2020). Areas where agriculture is not practiced, including alpine grassland and Ericaceous scrub, are threatened by intense grazing pressure, with Ericaceous forests further threatened by logging for fuelwood (Wesche et al., 2000; AWF, 2015). The Simen Mountains are overgrazed, with rates currently viewed as 14 times the sustainable rate (IUCN, 2020). In response to this, a Grazing Pressure Reduction Strategy was implemented across the park in 2015 (AWF, 2015). This designated 92% of the NP as a no grazing zone, with 8% of this area, predominately located in the south of the NP boundary, designated as limited/controlled resource use areas (AWF, 2015). These interventions have led to a visible increase in vegetation cover, however the effectiveness of no grazing zones is variable (IUCN, 2020).

Climate change poses a wider future threat to the IPA. Alpine areas are among the environments most likely to be impacted by climate change as mountaintop specialist species are already at the edge of the climactic envelope. Although Ethiopia has the largest extent of Afroalpine habitats in Africa, climate change is predicted to reduce these remaining fragmented and isolated ‘sky-island’ habitats (IPCC, 2019), and changes to precipitation and temperatures have already been observed at the site (UNESCO, 2022). Modelling of habitat suitability under conservative climate predictions has revealed large reductions in habitats suitable for Afroalpine species within this century (Chala et al., 2016). Chala et al. (2016) modelled the response of Lobelia rhychopetalum, a charismatic species of Ethiopia's Afroalpine vegetation, to four climate scenarios and estimated a loss in climate space of c. 80%. Species are predicted to adapt to climate by migrating uphill (Chala et al., 2016) and the tree line in the SM has risen by c 100–150 m within the last century (Jacob et al., 2017). While this has been proposed to be a result of changing climate (IUCN, 2020), tree lines in the African tropics are strongly disturbed by human and livestock pressure, which makes it impossible to use them as a proxy for climate change as they are not at their climactic limit (Jacob et al., 2014). Further study is required to understand the potential impacts of future warming, altered precipitation, and consequently the incidence of fire, and how this will impact the flora of the IPA.

While fire affects most tropical alpine plant communities (Young, 1987), inappropriate fire regimes pose a threat to this IPA. Tropical alpine systems may burn naturally; however such fires occur at low intensity and infrequently at multi-decadal intervals (Keith et al., 2020). The fire history of the SM shows that fire is frequent in the landscape, occurring in a patchy mosaic over the site with an interval as frequent as every 1-5 years in some areas (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005; IUCN, 2020). Notably there recently was a severe, large-scale fire in 2019 which burned c 787 ha of Ericaceous belt (EB) and Alpine grassland on the plateau in the NP, most of which has recovered (IUCN, 2020). There is evidence that EB vegetation is fire adapted and will resprout with fire intervals of >3 years. Studies of fire in Ethiopia's Afroalpine regions have not found any obligate fire-dependant species, which contrasts to many systems that have a natural fire regime (Johansson et al., 2019). There is a plan to develop a fire management strategy for the park, however, this has not yet been initiated (IUCN, 2020). Long term monitoring and research into the impacts of fire regimes on vegetation dynamics at the site is needed to inform strategy.

Invasive species have not been properly assessed but were observed during the October 2009 UNESCO/IUCN mission to the SNP, with a new road development bringing ‘potential risks of introducing and spreading such invasive species (IUCN, 2020).

Ecosystem services

The Simen Mountains (SM) provide a wide range of important ecosystem services. This ecosystem benefits people living in the SM and beyond in many ways; locally the site is utilized as a source of food, animal feed, medicine, fuel wood, as well as having wide significance for flood mitigation and as a source of water and genetic resources (Keiner, 2000; EBI, 2022). Many of the communities in the SM are remote and chronically food insecure, thus wild-food plants are an important a coping mechanism in times of food shortage as well as a source for bush-medicines (Guinand & Lemessa, 2000). Utilization of the SM is limited in the NP boundary, with some grazing and sustainable resource use permitted in zones concentrated in the south of the park near settlements (AWF, 2015).

Like all alpine regions, the Simen mountains are a critical water source. Several rivers originate from the mountain, including the Jinbar, Menesha, Seraweka, as well as the Belegez and Wazla which are tributaries to the Tekeze River. The Tekeze provides a source of water for millions downstream in Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt. Additionally, native vegetation in the SM controls erosion by slowing and storing water, which leads to higher catchment quality and buffers against flooding in the lowlands (Miehe & Miehe, 1994; EBI, 2022).

The SM is one of Ethiopia’s main tourist attractions, and is highly frequented for its extraordinary natural beauty, biodiversity and cultural heritage (Puff & Nemomissa, 2005). Recently reported yearly tourist numbers range from c. 11,000-32,400 (UNESCO, 2015-2020). While there is significant potential for tourism revenue generated by the SM to be a source of income for local communities and conservation, current the infrastructure is inadequate to sustainably support such numbers. Any development of tourist infrastructure must be designed to have minimal adverse impact on the natural values and unique biodiversity at the site.

Site assessor(s)

Gabriella Hoban, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Iain Darbyshire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Sileshi Nemomissa, Addis Ababa University

Sebsebe Demissew, Addis Ababa University

Ermias Lulekal, Addis Ababa University

IPA criterion A species

| Species | Qualifying sub-criterion | ≥ 1% of global population | ≥ 5% of national population | 1 of 5 best sites nationally | Entire global population | Socio-economically important | Abundance at site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthopale aethiogermanica Ensermu | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Afrovivella semiensis (J.Gay ex A.Rich.) A.Berger | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Common |

| Alchemilla bachiti Hochst. ex Hauman & Balle | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Artemisia schimperi Sch.Bip. ex Engl. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Ceropegia sobolifera N.E.Br. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Cirsium straminispinum C.Jeffrey ex Cufod. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Crepis achyrophoroides Vatke | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Crepis tenerrima Sch.Bip. ex Oliv. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Crepis xylorrhiza Sch.Bip. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Crinipes abyssinicus (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Hochst. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Cyanotis polyrrhiza Hochst. ex Hassk. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Cyperus clandestinus Steud. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Disperis crassicaulis Rchb.f. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Disperis galerita Rchb.f. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Drimia simensis (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Stedje | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Echinops buhaitensis Mesfin | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Festuca gilbertiana E.B.Alexeev ex S.M.Phillips | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Festuca macrophylla Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Abundant |

| Inula arbuscula Delile | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Occasional |

| Kalanchoe quartiniana A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Lobelia schimperi Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Paronychia bryoides Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Pennisetum humile Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Phagnalon phagnaloides (Sch.Bip. ex A.Rich.) Cufod. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Pimpinella pimpinelloides (Hochst.) H.Wolff | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Poa pumilio Hochst. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Ranunculus distrias Steud. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Ranunculus simensis Fresen. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Ranunculus tembensis Fresen. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Saxifraga hederifolia Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Occasional |

| Sedum epidendrum Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Senecio farinaceus Sch.Bip. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Solanum hirtulum Steud. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Stachys hypoleuca Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Verbascum sedgwickianum (Schimp. ex Engl.) Hub.-Mor. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Verbascum stelurum Murb. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Euphorbia repetita Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Isolepis omissa J.Raynal | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Sisymbrium maximum Hochst. ex E.Fourn. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Euphorbia repetita Hochst. ex A.Rich. | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Asplenium balense Chaerle & Viane | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Occasional |

| Vernonia buchingeri (Steetz) Oliv. & Hiern | A(iii) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Gymnosporia cortii Pic.Serm. | A(iii) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Micromeria unguentaria Schweinf. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Cenchrus beckeroides (Leeke) ined. | A(iii) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Snowdenia mutica (Hochst.) Pilg. | A(iv) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

| Cineraria sebaldii Cufod. | A(iii) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

Acanthopale aethiogermanica Ensermu

Afrovivella semiensis (J.Gay ex A.Rich.) A.Berger

Alchemilla bachiti Hochst. ex Hauman & Balle

Artemisia schimperi Sch.Bip. ex Engl.

Ceropegia sobolifera N.E.Br.

Cirsium straminispinum C.Jeffrey ex Cufod.

Crepis achyrophoroides Vatke

Crepis tenerrima Sch.Bip. ex Oliv.

Crepis xylorrhiza Sch.Bip.

Crinipes abyssinicus (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Hochst.

Cyanotis polyrrhiza Hochst. ex Hassk.

Cyperus clandestinus Steud.

Disperis crassicaulis Rchb.f.

Disperis galerita Rchb.f.

Drimia simensis (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Stedje

Echinops buhaitensis Mesfin

Festuca gilbertiana E.B.Alexeev ex S.M.Phillips

Festuca macrophylla Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Inula arbuscula Delile

Kalanchoe quartiniana A.Rich.

Lobelia schimperi Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Paronychia bryoides Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Pennisetum humile Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Phagnalon phagnaloides (Sch.Bip. ex A.Rich.) Cufod.

Pimpinella pimpinelloides (Hochst.) H.Wolff

Poa pumilio Hochst.

Ranunculus distrias Steud. ex A.Rich.

Ranunculus simensis Fresen.

Ranunculus tembensis Fresen.

Saxifraga hederifolia Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Sedum epidendrum Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Senecio farinaceus Sch.Bip. ex A.Rich.

Solanum hirtulum Steud. ex A.Rich.

Stachys hypoleuca Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Verbascum sedgwickianum (Schimp. ex Engl.) Hub.-Mor.

Verbascum stelurum Murb.

Euphorbia repetita Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Isolepis omissa J.Raynal

Sisymbrium maximum Hochst. ex E.Fourn.

Euphorbia repetita Hochst. ex A.Rich.

Asplenium balense Chaerle & Viane

Vernonia buchingeri (Steetz) Oliv. & Hiern

Gymnosporia cortii Pic.Serm.

Micromeria unguentaria Schweinf.

Cenchrus beckeroides (Leeke) ined.

Snowdenia mutica (Hochst.) Pilg.

Cineraria sebaldii Cufod.

IPA criterion C qualifying habitats

| Habitat | Qualifying sub-criterion | ≥ 5% of national resource | ≥ 10% of national resource | 1 of 5 best sites nationally | Areal coverage at site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afroalpine grassland | C(iii) |  |

|

|

Afroalpine grassland

General site habitats

| General site habitat | Percent coverage | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Dry Forest |  |

Minor |

| Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Moist Montane Forest |  |

Minor |

| Shrubland - Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude Shrubland |  |

Major |

| Grassland - Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude Grassland |  |

Major |

| Rocky Areas - Rocky Areas [e.g. inland cliffs, mountain peaks] |  |

Minor |

| Wetlands (inland) - Alpine Wetlands [includes temporary waters from snowmelt] |  |

Minor |

Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Dry Forest

Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Moist Montane Forest

Shrubland - Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude Shrubland

Grassland - Subtropical/Tropical High Altitude Grassland

Rocky Areas - Rocky Areas [e.g. inland cliffs, mountain peaks]

Wetlands (inland) - Alpine Wetlands [includes temporary waters from snowmelt]

Land use types

| Land use type | Percent coverage | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Nature conservation |  |

Major |

| Agriculture (arable) |  |

Minor |

| Agriculture (pastoral) |  |

Major |

| Tourism / Recreation |  |

Minor |

| Harvesting of wild resources |  |

Minor |

Nature conservation

Agriculture (arable)

Agriculture (pastoral)

Tourism / Recreation

Harvesting of wild resources

Threats

| Threat | Severity | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture & aquaculture - Annual & perennial non-timber crops - Small-holder farming | Low | Past, not likely to return |

| Agriculture & aquaculture - Livestock farming & ranching - Small-holder grazing, ranching or farming | High | Ongoing - stable |

| Biological resource use - Gathering terrestrial plants | Medium | Ongoing - stable |

| Biological resource use - Logging & wood harvesting - Intentional use: subsistence/small scale (species being assessed is the target) [harvest] | Medium | Ongoing - trend unknown |

| Human intrusions & disturbance - War, civil unrest & military exercises | Medium | Past, likely to return |

| Natural system modifications - Fire & fire suppression | High | Ongoing - trend unknown |

| Climate change & severe weather | High | Ongoing - increasing |

| Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases - Invasive non-native/alien species/diseases | Low | Ongoing - trend unknown |

Agriculture & aquaculture - Annual & perennial non-timber crops - Small-holder farming

Agriculture & aquaculture - Livestock farming & ranching - Small-holder grazing, ranching or farming

Biological resource use - Gathering terrestrial plants

Biological resource use - Logging & wood harvesting - Intentional use: subsistence/small scale (species being assessed is the target) [harvest]

Human intrusions & disturbance - War, civil unrest & military exercises

Natural system modifications - Fire & fire suppression

Climate change & severe weather

Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases - Invasive non-native/alien species/diseases

Protected areas

| Protected area name | Protected area type | Relationship with IPA | Areal overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simien National Park | National Park | IPA encompasses protected/conservation area |  |

| Simien National Park | UNESCO World Heritage Site | IPA encompasses protected/conservation area |  |

Simien National Park

Simien National Park

Conservation designation

| Designation name | Protected area | Relationship with IPA | Areal overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simien Mountains National Park | Important Bird Area | protected/conservation area encompasses IPA |  |

| Simien Mountains National Park | Key Biodiversity Area | protected/conservation area encompasses IPA |  |

Simien Mountains National Park

Simien Mountains National Park

Management type

| Management type | Description | Year started | Year finished |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Area management plan in place | The General Management Plan (GMP) is in its final draft form and will consider the newly included wildlife habitats land of the Simien Mountains National Park | 2020 | 2029 |

| Protected Area management plan in place | A Grazing Management Strategy for the NP site was written by AWC and EWCA. Use zones for grazing, sustainable use as well as exclusion zones are outlined in the report. | 2015 |  |

Protected Area management plan in place

Protected Area management plan in place

Bibliography

Atlas of the Potential Vegetation of Ethiopia.

Google Earth Satellite Imagery

Plants of the Simen

Vegetation belts of the East African mountains

Svensk. Bot. Tidskr., Vol 45, page(s) 140-202

Evolution of the Afroalpine Flora

Biotropica, Vol 2, page(s) 16-23

'Paleoglaciated Landscapes in Simen and Other High-Mountain Areas of Ethiopia' in Billi, P: Landscapes and Landforms of Ethiopia

Towards a new management plan for the Simen Mountains National Park

Tree line dynamics in the tropical African highlands – identifying drivers and dynamics

Journal of Vegetation Science

'Zur oberen Waldgrenze in tropischen Gebirgen' Towards the upper treeline in tropical mountains

Phytocoenologia, Vol 24, page(s) 43-110

The Simen Mountains (Ethiopia): Comments on Plant Biodiversity, Endemism, Phytogeographical Affinities and Historical Aspects

Systematics and Geography of Plants, Vol 71(2)

History and evolution of the afroalpine flora: in the footsteps of Olov Hedberg

Alpine Botany, Vol 132, page(s) 65-87

Land cover dynamics in the Simien Mountains (Ethiopia), half a century after establishment of the National Park

Reg Environ Change, Vol 17, page(s) 777-787

Tropical alpine plant ecology

Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, Vol 18, page(s) 137-58

Modelling the distribution of Ethiopian plant taxa (not published)

National Ecosystem Assessment Of Ethiopia

Important Bird Area factsheet: Simien Mountains National Park

Composition and Endemicity of Plant Species in Simien Mountains National Park Flora, North Gondar, Northwestern Ethiopia

Ethiopian Journal of Natural and Computational Sciences, Vol 2(1), page(s) 301-310

Field Assessment Report: Food insecure areas along Tekeze River and in the Simien Mountains

Endemic medicinal plants of Ethiopia: Ethnomedicinal uses, biological activities and chemical constituents

Journal of Ethnopharmacology

Simien National Park Conservation Outlook Assessment

Simien Mountains National Park State of Conservation Reports

The Significance of Fire for Afroalpine Ericaceous Vegetation

Mountain Research and Development, Vol 20(4), page(s) 340-347

Simien Mountains National Park Grazing Pressure Reduction Strategy

Good-bye to tropical alpine plant giants under warmer climates? Loss of range and genetic diversity in Lobelia rhynchopetalum

Ecology and Evoluntion, Vol 6, page(s) 8931–8941

Change in heathland fire sizes inside vs. outside the Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia, over 50 years of fire-exclusion policy: lessons for REDD+

Ecology and Society, Vol 24(4)

Modeling Cultural Keystone Species for the Conservation of Biocultural Diversity in the Afroalpine

environments, Vol 9(12)

Recommended citation

Gabriella Hoban, Iain Darbyshire, Sileshi Nemomissa, Sebsebe Demissew, Ermias Lulekal (2025) Tropical Important Plant Areas Explorer: Simen Mountains (Ethiopia). https://tipas.kew.org/site/simien-mountains/ (Accessed on 14/03/2025)