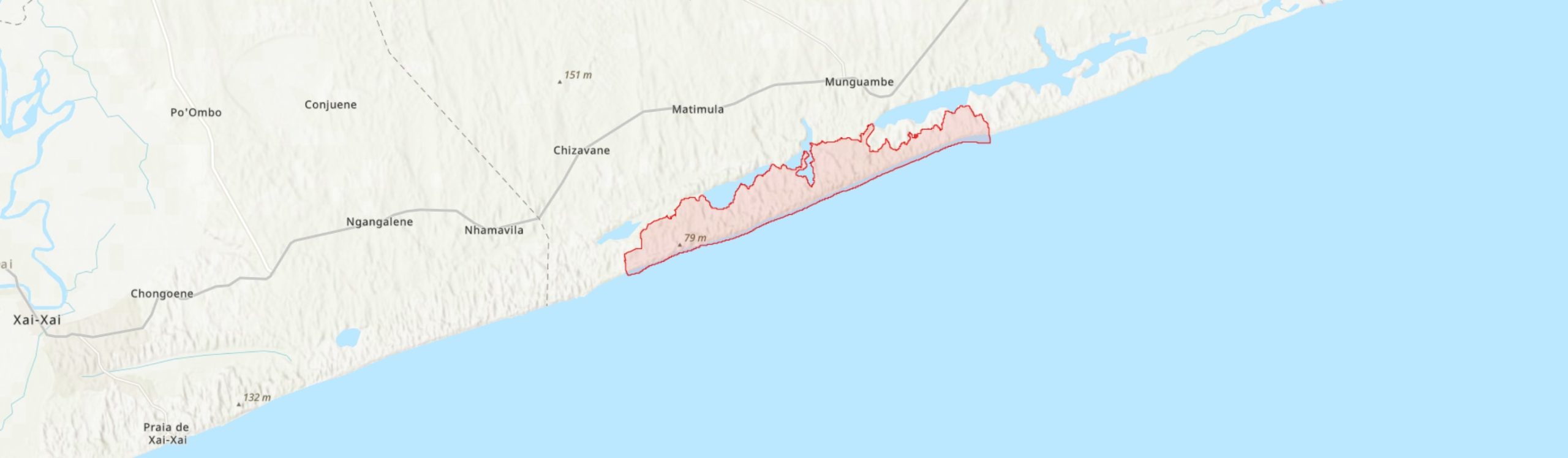

Country: Mozambique

Administrative region: Gaza (Province)

Central co-ordinates: 24.96651 S, 34.15002 E

Area: 60.3km²

Qualifying IPA Criteria

A(i)Site contains one or more globally threatened species

IPA assessment rationale

Chidenguele qualifies as an IPA under sub-criterion A(i), as it hosts important populations of one Endangered species, Ecbolium hastatum, two Vulnerable species, Raphia australis and Elaeodendron fruitcosum. As one of only a handful of sites from which R. australis is known, and as the most northerly and only site at which this species occurs in reed beds, Chidenguele is of great importance for the conservation of this Vulnerable palm species.

Six endemic species are known from this IPA, representing 1% of species from the national list of species of high conservation importance, below the 3% threshold required to meet sub-criterion B(ii).

Site description

Chidenguele is a coastal IPA, in Madlakazi District of Gaza Province. The site is situated around 2 km south-west of Chidenguele town and covers an area of 60 km2. This IPA encompasses high-quality coastal forest habitat, a stretch of 25 km along the coastline from Lago Matsambe in the east to Praia de Chiziane in the west. Much of this habitat is threatened throughout southern Mozambique by clearance for agriculture while the forests around Chidenguele are, in contrast, largely intact and therefore offer an opportunity to conserve this habitat type.

Beyond the coastal forests, Chidenguele IPA stretches into the intertidal zone, to include the sandstone platforms on which the Near Threatened seagrass, Thalassodendron leptocaule, grows. The coastal area, Praia do Chidenguele, is also a small tourist location with a number of lodges in the forests to the west of this IPA.

The site has also been delineated to include the inland floodplain and wetland habitat associated with the globally Vulnerable palm species, Raphia australis. Although only a small population of this species is present at this site, Chidenguele is one of the few sites from which this species is known globally and so is of great importance to the conservation of R. australis. For information, the R. australis habitat patches have been delineated as part of the site map, however, these should not be treated as core zones, as the entire site requires conservation attention to protect the important biodiversity here.

Botanical significance

Chidenguele has been delineated to cover one of the few sites known to host the Vulnerable palm, Raphia australis. R. australis is reliant on the wetland habitat within the core zones. Interestingly, unlike other sites further south where this species inhabits swamp or gallery forests, Raphia australis grows within reed beds at Chidenguele (Matimele et al. 2016). This site is also unique as the most northerly location within the species’ distribution. To-date only 10 individuals have been observed from this site, however, the area is poorly sampled and it is estimated that there are upwards of 20 individuals present (H. Matimele, pers. comm. 2021). Chidenguele represents one of the five best sites in Mozambique for this species, all of which are under heavy pressure from expanding agricultural land (Matimele 2016). The continued presence of R. australis at this site is of great importance to the overall resilience of the species.

The dune forests of Chidenguele are also of conservation importance, particularly in providing habitat for two globally threatened species- Ecbolium hastatum (EN) and Elaeodendron fruticosum (VU). E. hastatum is a rare species with a patchy distribution, known only from southern Mozambique at between 5 to 7 locations. The coastal dune thicket which this species is restricted to is known to be threatened by expansion of towns and tourism infrastructure (Darbyshire et al. 2018). Although only three individuals have been observed towards Praia de Chiziane (McCleland & Massingue 2018), there are likely more individuals around Chidenguele that have yet to be recorded. This IPA represents one of only three relatively secure sites for this species and, given that the AOO (area of occupancy) is only slightly above the Critically Endangered category threshold, is of great importance in preventing the extinction of this species.

Another threatened endemic Elaeodendron fruticosum (VU), also restricted to the coastal dunes of southern Mozambique, is present within this IPA. This species, like Ecbolium hastatum and Raphia australis, is also threatened by habitat loss through conversion of coastal dune habitat for agriculture.

In total, there are five endemic species recorded from this IPA, including Elaeodendron fruticosum and Ecbolium hastatum all of which occur within the coastal dune habitat. For one of these endemics, Baphia ovata (NT), Chidenguele may host one of the largest populations throughout this species’ range (Langa et al. 2019).

Chidenguele falls within the proposed Inhambane Centre of Plant Endemism (CoE) (Darbyshire et al. 2019) and some endemics present at this site, such as Baphia ovata and Elaeodendron fruticosum, have distributions limited only to this CoE. On a broader scale, Chidenguele also falls within the Coastal Forest of Eastern Africa Biodiversity Hotspot, covering some of the southernmost and westernmost forests within this hotspot. While the coastal forests and thickets of this site are largely intact and host a number of endemic species, possibly more than is currently known, there is insufficient data at this time to assess this habitat type across the proposed Inhambane CoE under the IPA criteria. However, it is possible that this site could also qualify under IPA criterion C in the future.

Delineation of this IPA has also included the intertidal zone, to cover the habitat of the Near Threatened seagrass Thalassodendron leptocaule. This species is known to form ecologically dominant stands on sandstone platforms with a number of epiphytic algae and marine invertebrates are dependent on the habitat created by T. leptocaule. However, through human disturbance and climate change this species may soon be threatened with extinction (Darbyshire et al. 2020). At Chidenguele the population may be relatively secure, however, increased footfall due to tourism at the site may pose a threat to this ecologically important species.

Habitat and geology

There have been few botanical studies made in the Chidenguele area, which have focused mainly on a small number of endemic or threatened species. A wide-scale botanical inventory is, however, yet to take place. The following habitat description is based primarily on a report by Impacto Lda. (2012) on Mandlakazi District.

Chidenguele encompasses a range of habitats spanning the intertidal zone and coastal dunes through to miombo woodlands inland, interspersed with a number of lagoons and wetlands associated with these lagoons. Underlying this site is Quaternary sedimentary geology, with mostly sandy soils and some recent alluvial deposits around the wetlands in the core zones and associated with the lagoons.

Furthest out to sea are the seagrass communities in the mid intertidal zone. Dominated by the seagrass Thalassodendron leptocaule (NT), these communities occur on sandstone platforms and are either submerged at all times or slightly exposed at low tide (Darbyshire et al. 2020). T. leptocaule provides habitat for a number of species- one study of this species in South Africa found 52 taxa of macroalgae and 204 macroinvertebrates living on a population of this seagrass (Browne et al. 2013). It is therefore likely that the seagrass around Chidenguele also supports a complex web of ecological interactions.

Moving into the coastal zone, the dune vegetation follows a successional gradient, with common pioneer species such as Cyperus maritimus, Ipomoea pes-caprae, Scaevola thunbergii and Sesuvium portulacastrum inhabiting the foredunes. Moving further inland, shrubby vegetation dominates, including species such as Diospyros rotundifolia and Grewia occidentalis var. litoralis. Encephalartos ferox subsp. ferox, assessed as Near Threatened at species level, has been recorded from sheltered valleys within the dune system. The dune thicket towards Praia de Chizaine has a low canopy and includes species such as Croton pseudopulchellus, Zanthoxylum delagoense, Manilkara concolor and Mimusops caffra in the canopy with a sparse understory that features Barleria repens. It is likely that dune thicket of this character is present throughout the dunes of this IPA. Dense coastal forest is present in some areas towards the back of the dune system. The coastal forests in this district are dominated by Afzelia quanzensis, Mimopsus caffra, Sideroxylon inerme and Ficus species.

Behind the coastal forest-thicket is habitat characterised by Lötter et al. (2021) as “Inharrime Coastal Palmveld”, a poorly drained area of open wooded grassland. Species include palms such as Phoenix reclinata, Hyphaene coriacea and Borassus aethiopum, alongside various grass species including several of genera Andropogon, Eragrostis and Hyparrhenia (Lötter et al. 2021). In drier areas, Brachystegia spiciformis dominates with species such as Albizia adianthifolia and Afzelia quanzensis occurring in regrowth following disturbance (Impacto 2012). Patches of reedbed wetlands, some of which are associated with the lagoons, are dominated by Phragmites australis and Typha capensis. These reedbeds provide important habitat for Raphia australis (VU) and this is the only site from which R. australis is known to grow in reedbeds (Matimele et al. 2016).

There are a number of pools around the wetland areas of the IPA, some of which appear seasonal from satellite imagery (Google Inc. 2020). Some of these pools have been reported to support Pandanus livingstonianus on the edges (Impacto 2012), although this species may be restricted to the larger bodies of water that retain water year-round. This species may be of note as some sources report it to be endemic to Mozambique (see Burrows et al. 2018), although the delimitation of this species is disputed.

The wetlands and lagoons are important sources of water for agriculture and, as such, a significant proportion of land bordering these areas is used for small-scale farming of crops such as sugar and rice. Much of the miombo in the north and east of this IPA, associated with urban expansion of Chidenguele, has also been converted to farmland. Agriculture in this area is largely for subsistence purposes and common crops include corn, beans, peanuts, cassava and sweet potatoes.

Conservation issues

Chidenguele does not fall within a protected area, Key Biodiversity Area or RAMSAR site. There are no known land management plans or local conservation initiatives within this IPA (Impacto Lda. 2012). However, between 2009 and 2010, a project funded by the Global Environment Facility was undertaken to promote community awareness about the value of biodiversity, specifically focussing on the shore of Lagoa Inhapavola, to the east of this IPA. Although much of the land surrounding this lake lies north-east of this IPA, there may be some indirect benefits to greater community awareness in the local area.

The main threat to the flora of this site is conversion of habitats for agriculture. Much of the northern and eastern areas of this IPA have been converted to agriculture. Most of this is done on a small-scale for subsistence purposes, with crops including corn, beans, peanuts, cassava and sweet potatoes. However, there are a small number of family-run farm businesses selling crops such as rice, cashews and vegetables. While it is true that clearing of land for agricultural expansion at this site has been limited in the last decade, there continues to be small-scale clearance and degradation of woodland and coastal forest within the IPA (Google Inc. 2020; World Resources Institute 2021). Of greatest concern is the farming of land in and around the wetlands of this site, with subsistence crops such as rice and sugarcane grown in these areas (H. Matimele, pers. comm. 2021). While the reliable supply of water in these wetlands supports higher agricultural yields, the water demand of agriculture also changes the hydrology of these wetlands, reducing seed recruitment for Raphia australis (VU) and weakening the long-term resilience of the population, particularly as this species flowers only once in its lifetime (Matimele et al. 2016).

Another major factor contributing to habitat loss is the establishment of tourism in the dune forests to the south-east of this IPA. Clearance of this dense vegetation for access roads and new facilities has taken place in recent decades (Google Inc. 2020). In addition, increased activity and footfall in the intertidal zone, linked to marine tourism activities, will potentially degrade of the habitats for Thalassodendron leptocaule (NT), a seagrass on which many marine species depend (Darbyshire et al. 2020). While the site has great tourism potential, and expansion of tourism could support livelihoods for local people, expansion of this sector near Chidenguele must be done responsibly to prevent unnecessary damage to the natural environment - particularly as the habitats here are a major draw for tourists. A number of hotels within and around this IPA already promote the natural scenery as part of their tourist offer. Tourism could, therefore, incentivise the protection of local habitats, with businesses dependent on these habitats to continue to attract visitors.

The fauna of this IPA has not been inventoried although the coastal areas and wetlands may be important for avifauna

Ecosystem services

This IPA currently encompasses several hotels and lodges (Google Inc. 2020). Much of the tourism focusses on beach and marine activities, however, a number of these hotels mention the nature-rich setting in promotional materials, with the intact coastal forests of particular interest. While there are unlikely any large charismatic mammals in the area (Impacto Lda. 2012), there could be some potential for bird-watching associated with coastal forest species, such as Rudd’s Apalis (LC) and Neergaard’s Sunbird (NT), known from southern Mozambique. An inventory of local bird species could help promote the nature tourism potential of the site.

The lagoons and wetlands are important water sources for both domestic use and for agriculture, although this may be at the expense of the wetland habitats within this IPA (Impacto Lda. 2012; Matimele et al. 2016).

The seagrass, Thalassodendron leptocaule, provides habitat for numerous marine organisms (Darbyshire et al. 2020). This habitat, along with coral reefs in the subtidal zone, may contribute to resource-rich, marine ecosystems on which artisanal fishing activities in the district depend (Impacto Lda. 2012).

There are no formal forestry operations in the area, however, wood is harvested for domestic timber and fuel needs (Impacto Lda. 2012).

Site assessor(s)

Sophie Richards, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Iain Darbyshire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

IPA criterion A species

| Species | Qualifying sub-criterion | ≥ 1% of global population | ≥ 5% of national population | 1 of 5 best sites nationally | Entire global population | Socio-economically important | Abundance at site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecbolium hastatum Vollesen | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Scarce |

| Raphia australis Oberm. & Strey | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Occasional |

| Elaeodendron fruticosum N.Robson | A(i) |  |

|

|

|

|

Unknown |

Ecbolium hastatum Vollesen

Raphia australis Oberm. & Strey

Elaeodendron fruticosum N.Robson

General site habitats

| General site habitat | Percent coverage | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Marine Neritic (Submergent Nearshore Continental Shelf or Oceanic Island) - Seagrass (Submerged) |  |

Minor |

| Marine Intertidal - Sandy Shoreline and/or Beaches, Sand Bars, Spits, etc. |  |

Minor |

| Marine Coastal/Supratidal - Coastal Sand Dunes |  |

Major |

| Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Dry Forest |  |

Major |

| Savanna - Moist Savanna |  |

Major |

| Wetlands (inland) - Seasonal/Intermittent Freshwater Marshes/Pools [under 8 ha] |  |

Minor |

| Wetlands (inland) - Bogs, Marshes, Swamps, Fens, Peatlands [generally over 8 ha] |  |

Minor |

| Wetlands (inland) - Permanent Freshwater Lakes [over 8 ha] |  |

Minor |

| Artificial - Terrestrial - Arable Land |  |

Minor |

Marine Neritic (Submergent Nearshore Continental Shelf or Oceanic Island) - Seagrass (Submerged)

Marine Intertidal - Sandy Shoreline and/or Beaches, Sand Bars, Spits, etc.

Marine Coastal/Supratidal - Coastal Sand Dunes

Forest - Subtropical/Tropical Dry Forest

Savanna - Moist Savanna

Wetlands (inland) - Seasonal/Intermittent Freshwater Marshes/Pools [under 8 ha]

Wetlands (inland) - Bogs, Marshes, Swamps, Fens, Peatlands [generally over 8 ha]

Wetlands (inland) - Permanent Freshwater Lakes [over 8 ha]

Artificial - Terrestrial - Arable Land

Land use types

| Land use type | Percent coverage | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture (arable) |  |

Major |

| Tourism / Recreation |  |

Minor |

Agriculture (arable)

Tourism / Recreation

Threats

| Threat | Severity | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Residential & commercial development - Housing & urban areas | Medium | Ongoing - trend unknown |

| Residential & commercial development - Tourism & recreation areas | Low | Ongoing - trend unknown |

| Agriculture & aquaculture - Annual & perennial non-timber crops - Small-holder farming | High | Ongoing - trend unknown |

| Human intrusions & disturbance - Recreational activities | Low | Ongoing - trend unknown |

Residential & commercial development - Housing & urban areas

Residential & commercial development - Tourism & recreation areas

Agriculture & aquaculture - Annual & perennial non-timber crops - Small-holder farming

Human intrusions & disturbance - Recreational activities

Management type

| Management type | Description | Year started | Year finished |

|---|---|---|---|

| No management plan in place |  |

|

No management plan in place

Bibliography

Google Earth Satellite Imagery

Global Forest Watch

Historical Vegetation Map and Red List of Ecosystems Assessment for Mozambique – Version 1.0 – Final report

Ecbolium hastatum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T120941569A120980108

An Assessment of the Distribution and Conservation Status of Endemic and Near Endemic Plant Species in Maputaland

Millettia ebenifera. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Epiphytic Seaweeds and Invertebrates Associated with South African Populations of the Rocky Shore Seagrass Thalassodendron leptocaule — a Hidden Wealth of Biodiversity.

African Journal of Marine Sciences, Vol 35, page(s) 523-531

Thalassodendron leptocaule. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T149255832A149275898

Perfil Ambiental e Mapeamento do Uso Actual da Terra nos Distritos da Zona Costeira De Moçambique: Distrito de Mandlakazi

Baphia ovata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T120960184A120980303

Raphia australis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T30359A85955288

New populations and a conservation assessment of Ecbolium hastatum Vollesen

Bothalia, Vol 48, page(s) 1-3 Available online

Recommended citation

Sophie Richards, Iain Darbyshire (2024) Tropical Important Plant Areas Explorer: Chidenguele (Mozambique). https://tipas.kew.org/site/chidenguele/ (Accessed on 27/07/2024)